Presence and Absence: Melancholia and Confusion in the Digital Age

A psychoanalytic perspective on the impact of navigating the virtual and real world, drawing on the direct experience of drone pilots in war zones.

Introduction

This essay draws attention to how today’s digital society transforms not only the material world (how wars are fought) but also how it changes our psycho-social world. Moving quickly between the virtual and real world changes how we relate psychologically and emotionally to our inner selves, to each other, and to the social contexts in which we live and work. I offer a psychoanalytic interpretation of how working across the virtual and physical realms creates dissonance, detachment, melancholy and confusion in the digital age.

The essay draws on two examples from digital war zones. The first is from US Air Force drone pilots operating in Iraq in 2015 from a home base in the USA, attacking and killing enemies ‘virtually’ and then returning to their homes and family lives after their ‘killing work’. The other example comes from a Ukrainian drone operator fighting on the front line against the Russian invasion in 2023. This essay reveals how emotions and effects are a life and death matter. In particular, the essay opens up the problem of working between the virtual and real world, and how this complicates our emotional and psychological experience of being present and absent. I will discuss the impacts reported by these drone operators and then make links to how moving between the virtual world and reality impacts us more generally.

Case Study 1. The experience of USA drone operators

In a New York Times article, drone operators living with their families in the US, went to work to kill and maim by operating drones in Iraq. This led to them suffering stress on such an epidemic scale that drone flights had to be cut back. Our affective, psychological and emotional states are not simply a direct reaction to our experience of the material world, our emotional states and the world we experience are entangled and symbiotic to each other. The material world shapes our affective state and vice versa. In this USA case example, drone pilots are heavily impacted by their work, which in turn impacts their families. Drone flights were seriously reduced due to high stress levels, (and perhaps the errors made by the pilots were also linked to their high stress levels, which was ignored in the NY article).

Drone pilots are worn down by the unique stresses of their work “We’re at an inflection point right now,” said Col. James Cluff, the commander of the Air Force’s 432nd Wing”

Putting aside the question of whether or not USA drone attacks are ethical, rational or desirable, I want to explore the impact of using computer technologies and operating in the virtual domain, and how easily we make wrong assumptions about the psycho-social dynamics that occur. Below, I will discuss three assumptions brought up in The New York Times article as well as two additional points that were not mentioned, but are just as relevent to the conversation.

Point 1

Assumption: Physical distance from the warzone makes the killing less real, and less emotionally stressful for the ‘pilot’.

Correction: Physical distance doesn’t make any significant difference, in fact, it may be worse. In some ways, the drone operator is closer to the killing and gore, because, unlike an airline pilot who sees the damage from a great height and speed whilst flying over the strike area, the drone operator revisits the site and the video replays are studied in close up detail to assess the strike. Whilst the drone operator is thousands of miles away, emotionally they may be a lot closer to the consequences and violence inflicted on others by their actions. This is particularly horrifying when innocent civilians and children or their own men get killed in error.

Point 2

Assumption: ‘Virtual’ killing mediated through a computer screen is less ‘real’ and therefore less stressful than when in the warzone.

Correction: The killing appears to be no-less real in its impact on the operators.

‘ A Defense Department study in 2013, the first of its kind, found that drone pilots had experienced mental health problems like depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder at the same rate as pilots of manned aircraft who were deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan.’

As mentioned in point 1, the close-up replaying of the killing can make it more real, and the assumption that it’s like a fantasy war game seems to underestimate our human capacity to differentiate between reality and fantasy games. Perhaps in reverse when a susceptible person plays fantasy war games they may be more vulnerable to shoot up a school or commit a terrorist act because their real and virtual worlds are blurred, but mature drone operators seem as equally vulnerable to stress as ‘real’ pilots, suggesting that they know the difference at a deep level.

Point 3

Assumption: Being close to family and community gives the drone operator more support.

Correction: The stress of transitioning on a daily basis between war and Walmart, killing at work after dropping the kids off at school; seems far too difficult to manage psychologically. The problem is increased a) because whilst air pilots are deployed to a war zone for a limited time period, the drone operators are ‘perpetually deployed’ there is no looking forward to an end or a break, and b) because being deployed with a band of brothers/sisters in a war zone provides certain rituals and camaraderie that helps contain the stress.

Having our folks make that mental shift every day, driving into the gate and thinking, ‘All right, I’ve got my war face on, and I’m going to the fight,’ and then driving out of the gate and stopping at Walmart to pick up a carton of milk … and the fact that you can’t talk about most of what you do at home….

Point 4

The impact of killing whilst being free from danger oneself is a unique challenge.

This point isn’t mentioned in this NYT article, but I hypothesize that it might also be a factor in the drone operator’s stress. Pilots and soldiers in a warzone put their lives at risk and see colleagues at risk. Drone operators unleash violence upon others (and sometimes on innocent others) when their lives are free from danger. Does this make the killing more difficult to rationalize internally? Even if consciously they believe their killing is an act of a ‘just war’, perhaps unconsciously it is less easy to psychologically adjust to killing from afar. Does killing in rational, clinical circumstances, without the danger and risk, without the adrenalin of being in the warzone, without fear, make those doing the killing more psychologically vulnerable to unacknowledged guilt, a dissonance between what is believed and what is felt, leading to anxiety, stress and depression?

Point 5

A techno-utopian war without casualties might not be what it seems.

The Drone operators may also be experiencing the fallout from the techno-utopian idea that a clean, digital war can be fought without casualties (on our side) which represses and disavows the reality that war is always ugly and violent. When something is repressed it always returns, but not in obvious ways. The return of the repressed here may occur in three ways: 1) ‘Friendly fire’ and killing of their own soldiers by error, 2) the unleashing of arbitrary terrorist acts on civilians back home, that are almost impossible to defend against, and 3) the repression returns in the form of internalised ‘violence’ i.e. stress, depression, anxiety and other forms of mental illness as seen in the drone operators. There are always casualties!

Case Study 2. Ukrainian Drone Operator

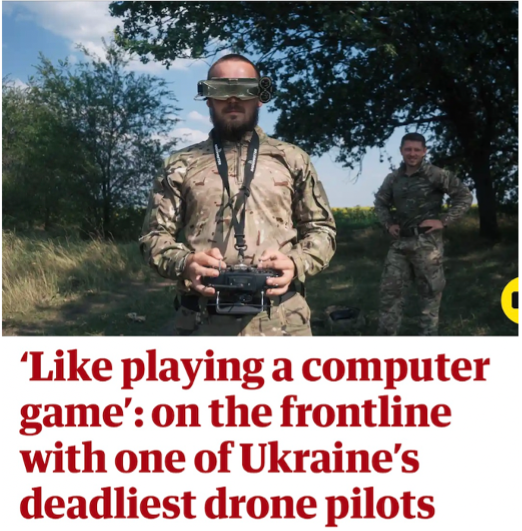

The second case study comes from a recent Guardian article that tells the story of a Ukranian drone operator fighting against Russian troops. While the article doesn’t go into depth on all the challenges, it does offer a different perspective on drone-operated digital warfare. Oleksandr is a drone operator working in danger with comrades on the frontline and drone operators are particularly targeted by Russians. Oleksandr describes his way of working and ‘prefers not to think of the lives that have been taken in the process….. “It’s like playing a computer game, you know?” Olexsandr says of his deadly and unenviable task, which, in the pervasive climate of war, has become almost shockingly routine for him. “It’s fun, you know? When it’s fun, when you relax, it’s easy. When you are tense, it is not possible to work correctly. Anyone can do it.”

What can we learn from this?

1. Olexsandr offers a classic dissociative defence, turning his deadly activity (as one of the most successful drone operators) into a ‘computer game’, explicitly linking it to the virtual world that millions of young men and women play to relax.

2. Preferring not to think about the death his drones bring about, might also be a useful defence against the fear of his own death. In war, this is a useful and perhaps necessary defence, but maybe it only works when you are in danger yourself, which was in contrast to the USA pilots.

3. Another difference between his activity and the USA pilots is that there is less focus on returning to the pictures that show the death and mayhem caused which helps the disassociation to take place.

4. The drone attacks are also different. The Ukrainian attacks use smaller hand-built drones, and target military vehicles rather than whole houses and villages as in Iraq/Afghanistan, which led to civilian loss and child loss in the USA examples.

5. Can dissociation last….Oleksandr is already in touch with the reality a little, perhaps it comes later?

Oleksandr has footage to prove his deadly work. A video from Friday morning shows Russian soldiers, unaware of the peril from above, firing over the trench at Ukrainian soldiers seeking to storm their position, only for one of Olexsandr’s Mavic 3 drones to make its lethal swoop.

It is not to brag, however, that he has agreed to meet by a sunflower field in Zaporizhzhia, near to where he was killing and maiming just a few hours earlier. “War is nothing to boast about,”

Discussion: Melancholia, presence and absence

Critics against drone attacks and those who planned the drone operations believed that drone operators are less psychologically present due to their physical absence, but it seems much more complex than this. Freud writing about melancholia says;

“It must be admitted that a loss has indeed occurred, without it being known what has been lost”[1]

Freud theorized that when mourning and grieving don't get fully processed, this leaves the person in a debilitating state of melancholia. This might help us understand the psycho-social dynamics that occur when we are constantly working between the real and the virtual. When working in the virtual domain, loss occurs in many ways - sometimes due to physical separation and sometimes due to more nuanced factors. Whilst we feel the effect of the loss, we rarely recognize what is actually lost in translation between the virtual and physical domains. As Freud says, ‘we experience the feeling of a loss but are not sure what has actually been lost’ and therefore we cannot mourn it, leaving us with the experience of melancholia.

Loss can also be enhanced by presence. Just because we are not physically present, doesn't make us absent. Physical absence can also enhance our emotional presence, and our virtual presence can evoke an effect of loss. For example, the teenagers in constant contact with parents or friends on mobile devices and social media are virtually more present but may experience the loss of autonomy, freedom and personal space to be themselves. They are forever digitally tethered and surveyed by their parents/friends.

Another example is when making video calls with my children while working abroad. Our live presence on the screen is a joy, but at the same time, it enhances the absence. The loss we feel, because we are physically apart, is amplified because of the virtual screen presence. This experience of loss in turn paradoxically enhances an emotional presence within me. My children become more present emotionally to me which leads to my experiencing a greater loss of not being able to hug them. My absence from the family and home becomes ever more present within me. This cyclical reinforcing of emotions that dance between presence and absence, virtual and real is a condition of our digital times. Whilst digital natives perhaps find this normative, the question remains as to what it does emotionally and psychologically to us and to our relationships.

The USA drone operators experience a loss and melancholia that becomes somatised to depression or other mental health conditions. Perhaps Ukrainian drone pilots operating in the warzone process their killing and their own personal losses of being absent from family more fully because they have a tangible context to process this. For example, they share an experience of killing, danger and loss of fallen comrades which they collectively mourn.

The USA drone pilots’ loss is unrecognized and unnamed; they are at home so it’s easier right? I would suggest that their loss is of being active with fellow soldiers in the warzone- the adrenalin, the fear, the danger, the camaraderie and the rituals that enable soldiers at war to contextualize the meaning. Also, they experience the loss of being separate from civilian life during their ‘war work’, freed from the intimacies, desires and demands of family and home life.

The absence of the family is tough when deployed, but perhaps the presence of the family is tougher as it raises such inner conflicts and tensions. Finally, the unconscious guilt or dissonance that occurs when killing the other, when not in danger one-self perhaps inflicts another hidden loss. A loss of humanity and of self-esteem at an unconscious level, that cannot be integrated or spoken of, as it breaches the agreed narrative of fighting righteous war.

We have a lot of work to do to understand the dynamics of our unfolding digital world and the psycho-social meanings and implications it evokes. The blurring between the real and the virtual worlds is creating new dynamics that are not easy to read. When working on zoom, I can experience an ‘emotional crashing’ after delivering a coaching or leadership course. From intense and often emotional group work on the screen, I crash back into family or solitary time, with no transitional space to navigate this. The screen shuts down and I am left alone in an office with all the feelings swirling around. No transitional post-workshop coffees, debriefs, laughter and chats. No travel time back home whilst I consciously and unconsciously process my experience.

Assumptions about our emotional and psychological experience of physical distance and virtual engagement need constant re-working in this digital age.

Defences, disassociations and the meaning of presence and absence are key to our understanding of the fluid boundaries between virtual and real.

[1] Sigmund Freud, ‘Mourning and Melancholia’, in Collected Papers, Vol. XIV, trans. James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1957) p. 252.